Is a Rained Windowsill an Example of Contrast Art

Landscape with scene from the Odyssey, Rome, c. threescore–40 BCE

Landscape painting, also known every bit landscape fine art, is the delineation of natural scenery such as mountains, valleys, trees, rivers, and forests, especially where the primary bailiwick is a broad view—with its elements arranged into a coherent composition. In other works, landscape backgrounds for figures can still form an of import part of the work. Sky is almost always included in the view, and weather is ofttimes an element of the limerick. Detailed landscapes every bit a distinct subject are not institute in all artistic traditions, and develop when there is already a sophisticated tradition of representing other subjects.

Two master traditions bound from Western painting and Chinese fine art, going dorsum well over a 1000 years in both cases. The recognition of a spiritual element in landscape art is present from its beginnings in E Asian art, drawing on Daoism and other philosophical traditions, only in the West only becomes explicit with Romanticism.

Mural views in art may be entirely imaginary, or copied from reality with varying degrees of accurateness. If the primary purpose of a picture is to depict an actual, specific identify, especially including buildings prominently, it is called a topographical view.[1] Such views, extremely mutual as prints in the West, are often seen equally junior to fine art landscapes, although the stardom is not always meaningful; like prejudices existed in Chinese art, where literati painting normally depicted imaginary views, while professional artists painted real views.[2]

The word "landscape" entered the modern English language as landskip (variously spelt), an anglicization of the Dutch landschap, effectually the showtime of the 17th century, purely as a term for works of fine art, with its first use as a word for a painting in 1598.[3] Within a few decades it was used to depict vistas in poesy,[4] and somewhen as a term for real views. However the cognate term landscaef or landskipe for a cleared patch of country had existed in Old English, though information technology is not recorded from Middle English.[5]

History [edit]

Zhan Ziqian, Strolling About in Spring, a very early Chinese landscape, c. 600

The earliest forms of art around the globe describe little that could really be called mural, although ground-lines and sometimes indications of mountains, trees or other natural features are included. The earliest "pure landscapes" with no human figures are frescos from Minoan fine art of effectually 1500 BCE.[6]

Hunting scenes, especially those set in the enclosed vista of the reed beds of the Nile Delta from Ancient Arab republic of egypt, tin requite a strong sense of place, but the emphasis is on individual institute forms and homo and fauna figures rather than the overall landscape setting. The frescos from the Tomb of Nebamun, now in the British Museum (c. 1350 BC), are a famous case.

For a coherent depiction of a whole landscape, some rough system of perspective, or scaling for distance, is needed, and this seems from literary evidence to have first been developed in Ancient Hellenic republic in the Hellenistic period, although no large-scale examples survive. More than aboriginal Roman landscapes survive, from the 1st century BCE onwards, especially frescos of landscapes decorating rooms that have been preserved at archaeological sites of Pompeii, Herculaneum and elsewhere, and mosaics.[vii]

The Chinese ink painting tradition of shan shui ("mountain-water"), or "pure" landscape, in which the merely sign of human life is usually a sage, or a glimpse of his hut, uses sophisticated landscape backgrounds to figure subjects, and landscape art of this menses retains a classic and much-imitated status inside the Chinese tradition.

Both the Roman and Chinese traditions typically show chiliad panoramas of imaginary landscapes, generally backed with a range of spectacular mountains – in Communist china often with waterfalls and in Rome often including sea, lakes or rivers. These were often used, every bit in the case illustrated, to span the gap between a foreground scene with figures and a afar panoramic vista, a persistent trouble for mural artists. The Chinese style by and large showed only a afar view, or used dead footing or mist to avert that difficulty.

A major dissimilarity between landscape painting in the W and East Asia has been that while in the Westward until the 19th century it occupied a low position in the accustomed hierarchy of genres, in Eastern asia the archetype Chinese mountain-water ink painting was traditionally the about prestigious form of visual art. Aesthetic theories in both regions gave the highest condition to the works seen to crave the most imagination from the creative person. In the West this was history painting, only in East Asia information technology was the imaginary landscape, where famous practitioners were, at least in theory, amateur literati, including several Emperors of both Red china and Japan. They were often also poets whose lines and images illustrated each other.[8]

Notwithstanding, in the West, history painting came to require an extensive mural background where appropriate, so the theory did not entirely piece of work confronting the evolution of landscape painting – for several centuries landscapes were regularly promoted to the status of history painting by the addition of pocket-sized figures to make a narrative scene, typically religious or mythological.

Western tradition [edit]

Medieval [edit]

In early Western medieval fine art interest in landscape disappears nearly entirely, kept alive just in copies of Tardily Antique works such as the Utrecht Psalter; the terminal reworking of this source, in an early on Gothic version, reduces the previously extensive landscapes to a few trees filling gaps in the composition, with no sense of overall space.[9] A revival in involvement in nature initially mainly manifested itself in depictions of small gardens such as the Hortus Conclusus or those in millefleur tapestries. The frescos of figures at work or play in front of a background of dense copse in the Palace of the Popes, Avignon are probably a unique survival of what was a mutual subject area.[ten] Several frescos of gardens have survived from Roman houses like the Villa of Livia.[eleven]

During the 14th century Giotto di Bondone and his followers began to acknowledge nature in their work, increasingly introducing elements of the landscape as the background setting for the activity of the figures in their paintings.[12] Early on in the 15th century, landscape painting was established as a genre in Europe, every bit a setting for human action, oft expressed in a religious subject, such every bit the themes of the Residual on the Flight into Egypt, the Journeying of the Magi, or Saint Jerome in the Desert. Luxury illuminated manuscripts were very important in the early evolution of landscape, especially series of the Labours of the Months such as those in the Très Riches Heures du Duc de Drupe, which conventionally showed small genre figures in increasingly large landscape settings. A particular advance is shown in the less well-known Turin-Milan Hours, now largely destroyed by burn down, whose developments were reflected in Early on Netherlandish painting for the remainder of the century. The artist known as "Mitt G", probably one of the Van Eyck brothers, was especially successful in reproducing furnishings of light and in a natural-seeming progression from the foreground to the afar view.[thirteen] This was something other artists were to discover difficult for a century or more, ofttimes solving the trouble by showing a landscape background from over the peak of a parapet or window-sill, every bit if from a considerable height.[fourteen]

Renaissance [edit]

Landscape backgrounds for various types of painting became increasingly prominent and skillful during the 15th century. The period around the end of the 15th century saw pure mural drawings and watercolours from Leonardo da Vinci, Albrecht Dürer, Fra Bartolomeo and others, but pure mural subjects in painting and printmaking, still small-scale, were starting time produced by Albrecht Altdorfer and others of the German Danube School in the early 16th century.[15] However, the outsides of the wings of a triptych by Gerard David, dated to "about 1510-15", are the earliest from the Low Countries, and possibly in Europe.[16] At the same time Joachim Patinir in the Netherlands developed the "world mural" a fashion of panoramic landscape with minor figures and using a high aeriform viewpoint, that remained influential for a century, beingness used and perfected past Pieter Brueghel the Elder. The Italian development of a thorough system of graphical perspective was now known all over Europe, which allowed large and circuitous views to be painted very effectively.

Titian, La Vierge au Lapin à la Loupe (The Virgin of the Rabbit), 1530, Louvre, Paris. Idealized Italianate landscape groundwork.

Landscapes were idealized, generally reflecting a pastoral ideal drawn from classical verse which was first fully expressed by Giorgione and the young Titian, and remained associated above all with hilly wooded Italian landscape, which was depicted by artists from Northern Europe who had never visited Italian republic, merely equally obviously-dwelling literati in China and Japan painted vertiginous mountains. Though oftentimes young artists were encouraged to visit Italy to experience Italian lite, many Northern European artists could brand their living selling Italianate landscapes without ever bothering to brand the trip. Indeed, certain styles were then popular that they became formulas that could be copied again and once again.[17]

The publication in Antwerp in 1559 and 1561 of ii series of a total of 48 prints (the Pocket-sized Landscapes) after drawings by an anonymous artist referred to as the Primary of the Small-scale Landscapes signaled a shift abroad from the imaginary, distant landscapes with religious content of the world landscape towards close-up renderings at eye-level of identifiable state estates and villages populated with figures engaged in daily activities. By abandoning the panoramic viewpoint of the earth landscape and focusing on the humble, rural and even topographical, the Small Landscapes gear up the stage for Netherlandish landscape painting in the 17th century. After the publication of the Small-scale Landscapes, mural artists in the Low Countries either continued with the world landscape or followed the new mode presented by the Small Landscapes.[18]

17th and 18th centuries [edit]

The popularity of exotic landscape scenes can be seen in the success of the painter Frans Post, who spent the balance of his life painting Brazilian landscapes after a trip there in 1636–1644. Other painters who never crossed the Alps could make money selling Rhineland landscapes, and nonetheless others for amalgam fantasy scenes for a particular committee such as Cornelis de Man's view of Smeerenburg in 1639.

Compositional formulae using elements like the repoussoir were evolved which remain influential in modern photography and painting, notably by Poussin[xix] and Claude Lorrain, both French artists living in 17th century Rome and painting largely classical subject area-thing, or Biblical scenes set in the same landscapes. Unlike their Dutch contemporaries, Italian and French landscape artists still most often wanted to keep their classification within the hierarchy of genres as history painting past including modest figures to stand for a scene from classical mythology or the Bible. Salvator Rosa gave picturesque excitement to his landscapes by showing wilder Southern Italian country, often populated past banditi.[20]

Dutch Gilded Age painting of the 17th century saw the dramatic growth of landscape painting, in which many artists specialized, and the development of extremely subtle realist techniques for depicting light and conditions. There are different styles and periods, and sub-genres of marine and beast painting, as well as a distinct style of Italianate landscape. Near Dutch landscapes were relatively small, merely landscapes in Flemish Baroque painting, still usually peopled, were often very large, above all in the series of works that Peter Paul Rubens painted for his own houses. Mural prints were also pop, with those of Rembrandt and the experimental works of Hercules Seghers usually considered the finest.

The Dutch tended to make smaller paintings for smaller houses. Some Dutch landscape specialties named in period inventories include the Batalje, or battle-scene;[21] the Maneschijntje,[22] or moonlight scene; the Bosjes,[23] or woodland scene; the Boederijtje, or farm scene,[24] and the Dorpje or village scene.[25] Though not named at the fourth dimension equally a specific genre, the popularity of Roman ruins inspired many Dutch mural painters of the period to paint the ruins of their ain region, such as monasteries and churches ruined later the Beeldenstorm.[26]

Jacob van Ruisdael is considered the most versatile of all Dutch Golden Age landscape painters.[27] The popularity of landscapes in kingdom of the netherlands was in part a reflection of the virtual disappearance of religious painting in a Calvinist society, and the decline of religious painting in the 18th and 19th centuries all over Europe combined with Romanticism to give landscapes a much greater and more prestigious place in 19th-century fine art than they had assumed earlier.

In England, landscapes had initially been mostly backgrounds to portraits, typically suggesting the parks or estates of a landowner, though mostly painted in London by an artist who had never visited his sitter'due south rolling acres. The English tradition was founded by Anthony van Dyck and other mostly Flemish artists working in England, only in the 18th century the works of Claude Lorrain were keenly collected and influenced not only paintings of landscapes, but the English language landscape gardens of Capability Brown and others.

In the 18th century, watercolour painting, mostly of landscapes, became an English specialty, with both a buoyant market for professional person works, and a large number of amateur painters, many post-obit the popular systems found in the books of Alexander Cozens and others. By the beginning of the 19th century the English artists with the highest modern reputations were mostly dedicated landscape painters, showing the wide range of Romantic interpretations of the English language landscape found in the works of John Lawman, J.M.Due west. Turner and Samuel Palmer. However all these had difficulty establishing themselves in the gimmicky fine art market, which all the same preferred history paintings and portraits.[28]

In Europe, equally John Ruskin said,[29] and Sir Kenneth Clark confirmed, landscape painting was the "chief artistic creation of the nineteenth century", and "the dominant fine art", with the result that in the following flow people were "apt to assume that the appreciation of natural beauty and the painting of landscape is a normal and indelible role of our spiritual activity"[30] In Clark'southward analysis, underlying European ways to convert the complication of landscape to an idea were 4 fundamental approaches: the acceptance of descriptive symbols, a curiosity nigh the facts of nature, the creation of fantasy to abate deep-rooted fears of nature, and the belief in a Gilded Age of harmony and social club, which might be retrieved.

The 18th century was also a keen historic period for the topographical impress, depicting more than or less accurately a real view in a style that landscape painting rarely did. Initially these were mostly centred on a edifice, but over the grade of the century, with the growth of the Romantic movement pure landscapes became more mutual. The topographical impress, often intended to be framed and hung on a wall, remained a very popular medium into the 20th century, but was oft classed equally a lower grade of art than an imagined landscape.

Landscapes in watercolour on paper became a distinct specialism, above all in England, where a particular tradition of talented artists who merely, or near entirely, painted mural watercolours developed, equally it did not in other countries. These were very ofttimes real views, though sometimes the compositions were adjusted for creative effect. The paintings sold relatively cheaply, but were far quicker to produce. These professionals could augment their income by grooming the "armies of amateurs" who also painted.[31]

Leading artists included John Robert Cozens, Francis Towne, Thomas Girtin, Michael Angelo Rooker, William Pars, Thomas Hearne, and John Warwick Smith, all in the late 18th century, and John Glover, Joseph Mallord William Turner, John Varley, John Sell Cotman, Anthony Copley Fielding, Samuel Palmer in the early on 19th.[32]

19th and 20th centuries [edit]

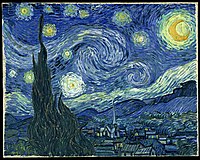

The Romantic movement intensified the existing interest in landscape art, and remote and wild landscapes, which had been one recurring element in earlier landscape art, now became more prominent. The German language Caspar David Friedrich had a distinctive manner, influenced past his Danish training, where a distinct national manner, cartoon on the Dutch 17th-century case, had adult. To this he added a quasi-mystical Romanticism. French painters were slower to develop mural painting, but from about the 1830s Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot and other painters in the Barbizon School established a French landscape tradition that would go the most influential in Europe for a century, with the Impressionists and Post-Impressionists for the first time making landscape painting the main source of general stylistic innovation across all types of painting.

The nationalism of the new United Provinces had been a factor in the popularity of Dutch 17th-century mural painting and in the 19th century, as other nations attempted to develop distinctive national schools of painting, the endeavor to express the special nature of the landscape of the homeland became a general tendency. In Russian federation, equally in America, the gigantic size of paintings was itself a nationalist statement.

In Spain, the main promoter of the genre was the Belgium-born painter Carlos de Haes, 1 of the about active mural professors at the Academy of Fine Arts of San Fernando in Madrid since 1857. After studying with the great Flemish landscape masters, he developed his technique to paint outdoors.[33] Back in Kingdom of spain, Haes took his students with him to paint in the countryside; under his educational activity the "painters proliferated and took advantage of the new railway arrangement to explore the furthest corners of the nation'due south topography."[34] [35]

In the United States, the Hudson River School, prominent in the middle to belatedly 19th century, is probably the all-time-known native development in landscape art. These painters created works of mammoth scale that attempted to capture the epic scope of the landscapes that inspired them. The piece of work of Thomas Cole, the school's mostly best-selling founder, has much in common with the philosophical ideals of European landscape paintings — a kind of secular faith in the spiritual benefits to be gained from the contemplation of natural dazzler. Some of the afterward Hudson River School artists, such every bit Albert Bierstadt, created less comforting works that placed a greater emphasis (with a great deal of Romantic exaggeration) on the raw, even terrifying power of nature. Frederic Edwin Church building, a educatee of Cole, synthesized the ideas of his contemporaries with those of European Erstwhile Masters and the writings of John Ruskin and Alexander von Humboldt to become the foremost American landscape painter of the century.[36] The best examples of Canadian landscape art can be plant in the works of the Group of Seven, prominent in the 1920s.[37]

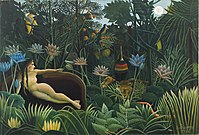

Although certainly less ascendant in the period after World War I, many significant artists still painted landscapes in the wide variety of styles exemplified by Edvard Munch, Georgia O'Keeffe, Charles E. Burchfield, Neil Welliver, Alex Katz, Milton Avery, Peter Doig, Andrew Wyeth, David Hockney and Sidney Nolan.

Gallery [edit]

East Asian tradition [edit]

China [edit]

Courtroom style panorama Along the River During the Qingming Festival, an 18th-century copy of 12th century Song Dynasty original by Chinese artist Zhang Zeduan. Zhang's original painting is revered by scholars as "ane of Chinese civilization'south greatest masterpieces."[38] The coil begins at the correct end, and culminates higher up as the Emperor boards his yacht to join the festive boats on the river. Note the exceptionally large viewing stones placed at the far border of the inlet.

Kuo Hsi, Immigration Fall Skies over Mountains and Valleys, Northern Song Dynasty c. 1070, detail from a horizontal scroll.[39]

Ma Yuan (Chinese: 馬遠, 1160–1225), Dancing and Singing (Peasants Returning from Piece of work, Chinese: 踏歌圖), 13th century, Southern Song (Chinese), Nerveless in the Palace Museum.

Dong Qichang, Landscape 1597. Dong Qichang was a loftier-ranking just cantankerous Ming civil retainer, who valued expressiveness over delicacy, with collector's seals and poems.

Landscape painting has been chosen "China'due south greatest contribution to the art of the world",[40] and owes its special character to the Taoist (Daoist) tradition in Chinese culture.[41] William Watson notes that "It has been said that the role of landscape art in Chinese painting corresponds to that of the nude in the west, every bit a theme unvarying in itself, but fabricated the vehicle of infinite nuances of vision and feeling".[42]

In that location are increasingly sophisticated landscape backgrounds to figure subjects showing hunting, farming or animals from the Han dynasty onwards, with surviving examples generally in rock or clay reliefs from tombs, which are presumed to follow the prevailing styles in painting, no incertitude without capturing the full effect of the original paintings.[43] The exact status of the later copies of reputed works past famous painters (many of whom are recorded in literature) before the 10th century is unclear. Ane example is a famous 8th-century painting from the Imperial collection, titled The Emperor Ming Huang traveling in Shu. This shows the entourage riding through vertiginous mountains of the blazon typical of later paintings, but is in full color "producing an overall pattern that is almost Persian", in what was evidently a popular and fashionable court fashion.[44]

The decisive shift to a monochrome landscape style, almost devoid of figures, is attributed to Wang Wei (699-759), also famous as a poet; by and large simply copies of his works survive.[45] From the 10th century onwards an increasing number of original paintings survive, and the all-time works of the Song Dynasty (960–1279) Southern School remain among the about highly regarded in what has been an uninterrupted tradition to the present twenty-four hours. Chinese convention valued the paintings of the apprentice scholar-gentleman, often a poet as well, over those produced past professionals, though the situation was more circuitous than that.[46] If they include whatsoever figures, they are very often such persons, or sages, contemplating the mountains. Famous works have accumulated numbers of scarlet "appreciation seals", and often poems added by later owners - the Qianlong Emperor (1711–1799) was a prolific adder of his own poems, post-obit earlier Emperors.

The shan shui tradition was never intended to correspond actual locations, even when named after them, every bit in the convention of the Eight Views.[47] A different mode, produced by workshops of professional court artists, painted official views of Imperial tours and ceremonies, with the principal accent on highly detailed scenes of crowded cities and grand ceremonials from a loftier viewpoint. These were painted on scrolls of enormous length in bright color (example below).

Chinese sculpture also achieves the difficult feat of creating effective landscapes in 3 dimensions. There is a long tradition of the appreciation of "viewing stones" - naturally formed boulders, typically limestone from the banks of mountain rivers that has been eroded into fantastic shapes, were transported to the courtyards and gardens of the literati. Probably associated with these is the tradition of carving much smaller boulders of jade or another semi-gem into the shape of a mountain, including tiny figures of monks or sages. Chinese gardens also developed a highly sophisticated aesthetic much earlier than those in the W; the karensansui or Japanese dry garden of Zen Buddhism takes the garden even closer to being a work of sculpture, representing a highly bathetic mural.

-

Detail from the hand scroll Pure and Remote View of Streams and Mountains, 1 of Xia Gui's almost important works, 13th century Cathay

-

Li Kan, Bamboos and Rock c. 1300 Advert., People's republic of china

-

Tang Yin, A Fisher in Autumn, 1523 AD., China

-

Shen Zhou, Poet on a Mountain c. 1500. Painting and poem by Shen Zhou: "White clouds encircle the mountain waist similar a sash,/Stone steps mountain high into the void where the narrow path leads far./Alone, leaning on my rustic staff I gaze idly into the altitude./My longing for the notes of a flute is answered in the murmurings of the gorge."[50]

-

Cai Han and Jin Xiaozhu, Fall Flowers and White Pheasants, 17th century, Cathay.

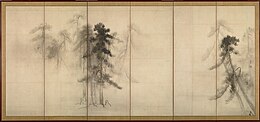

Japan [edit]

4 from a set of sixteen sliding room partitions made for a 16th-century Japanese abbot. Typically for later Japanese landscapes, the main focus is on a feature in the foreground.

Japanese art initially adapted Chinese styles to reverberate their interest in narrative themes in art, with scenes set in landscapes mixing with those showing palace or city scenes using the same high view point, cutting away roofs as necessary. These appeared in the very long yamato-e scrolls of scenes illustrating the Tale of Genji and other subjects, mostly from the 12th and 13th centuries. The concept of the admirer-amateur painter had little resonance in feudal Japan, where artists were generally professionals with a strong bond to their primary and his school, rather than the classic artists from the afar past, from which Chinese painters tended to depict their inspiration.[51] Painting was initially fully coloured, ofttimes brightly so, and the mural never overwhelms the figures who are often rather oversized.

The scene from the Biography of the Priest Ippen illustrated below is from a roll that in full measures 37.8 cm × 802.0 cm, for only i of twelve scrolls illustrating the life of a Buddhist monk; like their Western counterparts, monasteries and temples commissioned many such works, and these take had a better take chances of survival than ladylike equivalents.[52] Fifty-fifty rarer are survivals of landscape byōbu folding screens and hanging scrolls, which seem to take mutual in court circles - the Tale of Genji has an episode where members of the court produce the best paintings from their collections for a competition. These were closer to Chinese shan shui, but withal fully coloured.[53]

Many more pure landscape subjects survive from the 15th century onwards; several key artists are Zen Buddhist clergy, and worked in a monochrome style with greater emphasis on brush strokes in the Chinese way. Some schools adopted a less refined manner, with smaller views giving greater emphasis to the foreground. A type of epitome that had an indelible appeal for Japanese artists, and came to be chosen the "Japanese mode", is in fact first found in Communist china. This combines ane or more big birds, animals or trees in the foreground, typically to one side in a horizontal composition, with a wider landscape beyond, frequently simply covering portions of the background. Later versions of this style often dispensed with a landscape background birthday.

The ukiyo-e manner that developed from the 16th century onwards, first in painting and then in coloured woodblock prints that were cheap and widely available, initially concentrated on the human being figure, individually and in groups. Only from the late 18th century mural ukiyo-e developed under Hokusai and Hiroshige to become much the best known type of Japanese landscape art.[54]

-

Tenshō Shūbun, a Zen Buddhist monk, an early effigy in the revival of Chinese styles in Japan. Reading in a Bamboo Grove, 1446, Japan

-

Kanō Masanobu, 15th century founder of the Kanō schoolhouse, which dominated Japanese brush painting until the 19th century, Zhou Maoshu Appreciating Lotuses, hanging scroll[55]

-

The Bridge at Ubi a famous screen composition, found in many 16th or 17th century versions, showing the colourful abstracted style of the professional painters.[56] Yamato-eastward style of Japanese painting.

-

A scene from the Biography of the Priest Ippen yamato-e whorl, 1299

Persia and India [edit]

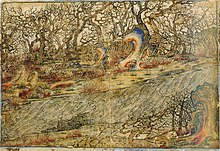

A rare pure mural in a Farsi miniature, with a river, Tabriz (?), 1st quarter of 14th century

Though in that location are some landscape elements in earlier art, the mural tradition of the Persian miniature actually begins in the Ilkhanid menses, largely under Chinese influence. Rocky mountainous country is preferred, which is shown full of animals and plants which are carefully and individually depicted, every bit are rock formations. The particular convention of the elevated viewpoint that developed in the tradition fills most of the vertical format picture spaces with the landscape, though clouds are also typically shown in the sky, shown in a curling convention drawn from Chinese fine art. Usually, everything seen is adequately shut to the viewer, and in that location are few distant views. Normally all mural images show narrative scenes with figures, but there are a few fatigued pure landscape scenes in albums.

Hindu painting had long fix scenes amid lush vegetation, equally many of the stories depicted demanded. Mughal painting combined this and the Farsi style, and in miniatures of royal hunts oft depicted wide landscapes. Scenes set during the monsoon rains, with dark clouds and flashes of lightning, are popular. Later, influence from European prints is axiomatic.

-

Khusraw discovers Shirin bathing in a puddle, a favourite scene, here from 1548. The black stream is silver that has oxidized.

-

Jahangir hunting with a falcon, in Western-style country.

-

The Gopis Plead with Krishna to Return Their Clothing, 1560s

Techniques [edit]

An 18th-century Korean version of the Chinese literati fashion by Jeong Seon who was unusual in often painting landscapes from life.

Near early landscapes are clearly imaginary, although from very early townscape views are clearly intended to correspond actual cities, with varying degrees of accuracy. Diverse techniques were used to simulate the randomness of natural forms in invented compositions: the medieval advice of Cennino Cennini to copy ragged crags from pocket-sized rough rocks was patently followed past both Poussin and Thomas Gainsborough, while Degas copied deject forms from a crumpled handkerchief held up confronting the light.[57] The organisation of Alexander Cozens used random ink blots to give the basic shape of an invented mural, to exist elaborated past the artist.[58]

The distinctive background view beyond Lake Geneva to the Le Môle summit in The Miraculous Draught of Fishes past Konrad Witz (1444) is often cited as the first Western rural mural to show a specific scene.[59] The landscape studies by Dürer clearly represent bodily scenes, which can exist identified in many cases, and were at least partly made on the spot; the drawings by Fra Bartolomeo too seem clearly sketched from nature. Dürer's finished works seem generally to use invented landscapes, although the spectacular bird's-heart view in his engraving Nemesis shows an actual view in the Alps, with additional elements. Several landscapists are known to have made drawings and watercolour sketches from nature, but the testify for early oil painting beingness done exterior is limited. The Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood made special efforts in this direction, but it was not until the introduction of prepare-mixed oil paints in tubes in the 1870s, followed by the portable "box easel", that painting en plein air became widely practiced.

A curtain of mountains at the back of the landscape is standard in wide Roman views and even more so in Chinese landscapes. Relatively little infinite is given to the sky in early works in either tradition; the Chinese often used mist or clouds betwixt mountains, and also sometimes testify clouds in the sky far earlier than Western artists, who initially mainly apply clouds equally supports or covers for divine figures or heaven. Both console paintings and miniatures in manuscripts usually had a patterned or golden "sky" or background above the horizon until virtually 1400, only frescos by Giotto and other Italian artists had long shown plain blue skies. The single surviving altarpiece from Melchior Broederlam, completed for Champmol in 1399, has a gilt sky populated not but by God and angels, only also a flight bird. A littoral scene in the Turin-Milan Hours has a sky overcast with advisedly observed clouds. In woodcuts a large bare infinite can cause the paper to sag during printing, so Dürer and other artists often include clouds or squiggles representing birds to avoid this.

The monochrome Chinese tradition has used ink on silk or paper since its inception, with a great emphasis on the individual brushstroke to define the ts'un or "wrinkles" in mountain-sides, and the other features of the mural. Western watercolour is a more tonal medium, even with underdrawing visible.

[edit]

Traditionally, landscape fine art depicts the surface of the Earth, but at that place are other sorts of landscapes, such as moonscapes.

- Skyscapes or Cloudscapes are depictions of clouds, weatherforms, and atmospheric weather.

- Moonscapes testify the mural of a moon.

- Seascapes depict oceans or beaches.

- Riverscapes depict rivers or creeks.

- Cityscapes or townscapes depict cities (urban landscapes).

- Battle scenes are a subdivision of armed forces painting which, when depicting a battle from afar, are fix within a landscape, seascape or even a cityscape.

- Hardscapes are paved over areas like streets and sidewalks, big business organisation complexes and housing developments, and industrial areas.

- Aerial landscapes draw a surface or ground from to a higher place, especially every bit seen from an airplane or spacecraft. (When the viewpoint is directly overhead, looking down, at that place is of course no depiction of a horizon or sky.) This genre tin can exist combined with others, every bit in the aerial cloudscapes of Georgia O'Keeffe, the aerial moonscapes of Nancy Graves, or the aerial cityscapes of Yvonne Jacquette.

- Inscapes are landscape-like (unremarkably surrealist or abstract) artworks which seek to convey the psychoanalytic view of the heed as a three-dimensional space. [For sources on this statement, run across the Inscape (visual art) article.]

- Vedute is the Italian term for view, and generally used for the painted landscape, often cityscapes which were a common 18th-century painting thematic.

- Landscape photography

Mural and modernism [edit]

-

-

-

-

-

Pablo Picasso, 1908, Paysage aux deux figures (Landscape with Two Figures), oil on canvas, lx ten 73 cm, Musée Picasso, Paris

-

Landscape art movements [edit]

Albrecht Altdorfer (c.1480–1538), Danube mural near Regensburg c. 1528, ane of the primeval Western pure landscapes. He was the leader of the Danube Schoolhouse in southern Federal republic of germany.

East Asian [edit]

- China

- Southern School, 8th–16th centuries, also known as the literati schoolhouse

- Four Masters of the Yuan Dynasty

- Four Masters of the Ming Dynasty

- Half dozen Masters of the early Qing flow, including the Four Wangs

- Nihon—frequently dynastic

- Tosa school 14th or 15th century to 19th

- Kanō school 15th to 19th centuries

- Hasegawa schoolhouse mid-16th to early 18th century

- Nanga ("Southern painting"), professionals in the Edo period influenced by Chinese literati painting - 17th to 19th centuries

Western [edit]

- Pre–19th century

- Danube school

- 19th and 20th century

- American Barbizon school

- American Impressionism

- Amsterdam Impressionism

- Barbizon School

- Düsseldorf schoolhouse of painting

- Carving revival

- Fauvism

- Group of Seven (Canada)

- Hague School

- Heidelberg School (Australia)

- Hoosier Grouping

- Hudson River School

- Impressionism

- Luminism (American)

- Luminism (Impressionism)

- Macchiaioli

- Neo-Impressionism

- Norwich School

- Peredvizhniki

- Pont-Aven School

- Post-Impressionism

- Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood

- The Ten

- Tonalism

- White Mount art

- Land art

See as well [edit]

- Claude glass

- Landscape architecture

- Vädersolstavlan

- Visual arts

- Skyscraper

- Category:Mural paintings

Notes [edit]

- ^ British Library, Topographical collections: an overview Archived 2010-07-21 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ British Library, Topographical prints and drawings: glossary of terms Archived 2010-07-12 at the Wayback Automobile.

- ^ OED "Landscape".

- ^ 1632, John Milton in L'Allegro is the earliest cited past the OED

- ^ The "scaef" coming from the Old English language "sceppan" significant "to shape". OED "Mural", Ingold, 126; Jackson, 156; Growth & Wilson, 2-3. Meet the "Etymology" section at Landscape for farther particular and references.

- ^ Honour & Fleming, 53. The simply very complete example, the Spring Fresco is now in the National Archaeological Museum, Athens, but there are several others with only creature figures, surviving in fragments.

- ^ Honour & Fleming, 150–151

- ^ A major theme throughout both Sickman and Paine. Encounter for instance Sickmann pp. 132–133, 182–186, 203–204, 319, 352–356, and Paine pp. 160–168, 235–243.

- ^ Clark, 17–18

- ^ Clark, 23-4; image, some other

- ^ At present removed to the Palazzo Massimo; Commons images Archived 2012-08-12 at the Wayback Auto

- ^ The landscape in Western Painting, Minneapolis Constitute of the Arts Archived 2009-07-25 at the Wayback Machine retrieved February 20, 2010

- ^ Clark, 31-2

- ^ Clark, 34-37

- ^ Honour & Fleming, 357, come across Wood for full coverage

- ^ Ainsworth, Maryan Wynn et al., From Van Eyck to Bruegel: Early Netherlandish Paintings in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, p. 302, 323; 2009, Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2009. ISBN 0-8709-9870-six, google books

- ^ See the mural piece of work of Barent Gael and Jacob van der Ulft, for example, whose Italian-style landscapes were formulaic copies, sometimes from prints.

- ^ Silver, p. 6-7

- ^ Poussin and The Heroic Landscape Archived 2011-09-28 at Wikiwix by Joseph Phelan, retrieved Dec 17, 2009

- ^ Clark, Affiliate 4

- ^ Run across the piece of work of Willem van de Velde the Younger, Huchtenburg and Pauwels van Hillegaert

- ^ Encounter the piece of work of Aert van der Neer

- ^ See the work of Jacques van Artois

- ^ Meet the work of Adriaen van Ostade

- ^ Encounter the work of Roelant Roghman

- ^ The ruins of Egmond Abbey were pop for a century.

- ^ Slive 17

- ^ Reitlinger, 74-75, 85-87

- ^ Modern Painters, volume three, "Of the novelty of mural".

- ^ Clark, xv–16.

- ^ Wilton & Lyles, eleven-28, 28 quoted

- ^ See Wilton & Lyles, for all these

- ^ Prado., Museo del (1996). The Prado Museum : [collection of paintings]. Bettagno, Alessandro. [Spain?]: Fonds Mercator. ISBN9061533716. OCLC 38061864.

- ^ Castilian literature. Current debates on Hispanism. Foster, David William., Altamiranda, Daniel., Urioste-Azcorra, Carmen. New York: Garland Pub. 2001. ISBN0815335628. OCLC 45223599.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ Spain beyond Espana : modernity, literary history, and national identity. Epps, Bradley S., Fernández Cifuentes, Luis. Lewisburg [PA]: Bucknell University Press. 2005. ISBN0838755836. OCLC 56617356.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ Kelly, Franklin (1989). Frederic Edwin Church (PDF). Washington: National Gallery of Fine art. p. 32. ISBN0-89468-136-two.

- ^ "Landscapes" in Virtual Vault Archived 2016-03-12 at the Wayback Machine, an online exhibition of Canadian historical fine art at Library and Archives Canada

- ^ Seno, Alexandra A. (2010-xi-02). "'River of Wisdom' is Hong Kong'south hottest ticket". The Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on 2017-07-09.

- ^ Sickman, 219-220

- ^ Sickman, 182

- ^ Sickman, 54-55

- ^ Watson, 72

- ^ Sickman, 82-84, and 186

- ^ Sickman, 182–183. p. 182 quoted.

- ^ Sickman, 184–186, and p. 203

- ^ Sickman, 304-305

- ^ Princeton University Art Museum Archived 2011-07-02 at the Wayback Car Wang Hong (human activity. ca. 1131-ca. 1161), Eight Views of the Xiao and Xiang Rivers (Xiao-Xiang ba jing)

- ^ Ebrey, Cambridge Illustrated History of Prc, 162.

- ^ Liu, l.

- ^ Sickman, 322.

- ^ Paine, 20-21

- ^ Paine, 153–154

- ^ Paine, 107–108

- ^ Paine, 269-272

- ^ Pierce, 177–182

- ^ Watson, 42

- ^ Clark, 26

- ^ "The art of Colorado's mural". 9 August 2007. Archived from the original on 2015-09-23. Retrieved 2015-09-04 . The Denver Post Landscape painting, The fine art of Colorado'south mural

- ^ Clark, 34

References [edit]

- Clark, Sir Kenneth, Landscape into Art, 1949, page refs to Penguin edn of 1961

- Dreikausen, Margret, "Aerial Perception: The Earth equally Seen from Aircraft and Spacecraft and Its Influence on Contemporary Art" (Associated Academy Presses: Cranbury, NJ; London; Mississauga, Ontario: 1985) ISBN 0-87982-040-three

- Growth, Paul Erling Wilson, Chris, Everyday America: Cultural Landscape Studies After J.B. Jackson, 2003, Academy of California Printing, ISBN 0520229614, 9780520229617, google books

- Hugh Honour and John Fleming, A World History of Art,1st edn. 1982 & later editions, Macmillan, London, folio refs to 1984 Macmillan 1st edn. paperback. ISBN 0-333-37185-two

- Ingold, Tim, "Being Alive", 2011, Routledge, Abingdon

- Jackson, John B., "The Word Itself", in The Cultural Geography Reader, Eds. Tim Oakes, Patricia Lynn Price, 2008, Routledge, ISBN 1134113161, 9781134113163

- Paine, Robert Treat, in: Paine, R. T. & Soper A, "The Art and Architecture of Japan", Pelican History of Art, 3rd ed 1981, Penguin (now Yale History of Art), ISBN 0-14-056108-0

- Plesu, Andrei, Pittoresque et mélancolie : Une analyse du sentiment de la nature dans la culture européenne, Somogy éditions d'art, 2007

- Reitlinger, Gerald; The Economic science of Taste, Vol I: The Rising and Fall of Motion-picture show Prices 1760-1960, Barrie and Rockliffe, London, 1961

- Sickman, Laurence, in: Sickman Fifty & Soper A, "The Art and Architecture of People's republic of china", Pelican History of Art, 3rd ed 1971, Penguin (at present Yale History of Art), LOC seventy-125675

- Silver, Larry, Peasant Scenes and Landscapes: The Ascent of Pictorial Genres in the Antwerp Art Market, Academy of Pennsylvania Press, 2012

- Slive, Seymour; Hoetink, Hendrik Richard, "Jacob van Ruisdael" (Abbeville Press: New York: 1981 ISBN 978-0-89659-226-1

- Virtual Vault, an online exhibition of Canadian historical art at Library and Athenaeum Canada

- Wilton, Andrew; T J Barringer; Tate Great britain (Gallery); Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts.; Minneapolis Establish of Arts. American sublime : landscape painting in the United States, 1820-1880 (Princeton, NJ : Princeton University Press, 2002)

- Watson, William, Way in the Arts of Mainland china, 1974, Penguin, ISBN 0140218637

- Watson, William, The Great Nihon Exhibition: Art of the Edo Period 1600–1868, 1981, Royal Academy of Arts/Weidenfeld & Nicolson

- Andrew Wilton & Anne Lyles, The Slap-up Age of British Watercolours, 1750–1880, 1993, Prestel, ISBN 3791312545

- Christopher Due south Wood, Albrecht Altdorfer and the Origins of Landscape, 1993, Reaktion Books, London, ISBN 0-948462-46-nine

Further reading [edit]

- American paradise: the world of the Hudson River school . New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art. 1987. ISBN9780870994968.

- Büttner, Nils. "Landscape Painting. A History", New/York/London 2006

- Fong, Wen C.; et al. (2008). Landscapes articulate and radiant: the art of Wang Hui (1632-1717) . New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art. ISBN9781588392916.

- The Landscape in Twentieth-Century American Art, Selections from the Metropolitan Museum of Art, Rizzoli, NY 1991, ISBN 0-8478-1303-7. Introduction by Robert Rosenblum, and essays by Lowery Stokes Sims and Lisa Messinger. [i]

External links [edit]

- History of European landscape painting, from the National Gallery of Art

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Landscape_painting

0 Response to "Is a Rained Windowsill an Example of Contrast Art"

Post a Comment